Phrases inspired by the letterpress

Written by Claire Scaramanga

Following a recent trip to Blist Hill Victorian Town (part of the Ironbridge Gorge Museum in Shropshire) we discover some of the phrases inspired by the letterpress.

This article has been assigned the following categories: Tips,

I recently visited Blist Hill Victorian Town (part of the Ironbridge Gorge Museum in Shropshire) with my family — including Iggy, our dog, as it is a dog friendly attraction. I usually opt for activities with higher adrenaline levels, but this was a surprisingly great day out. The whole experience is fully immersive and everyone was super friendly and eager to share their stories —whether that was learning about the importance of candles, saddling a massive Shire horse or having a sing-a-long in the pub.

I found the print shop with two working letter presses irresistible. With my daughter alongside, I proudly explained the reason behind the words uppercase and lowercase feeling smug that my design knowledge could finally pay off and make me look smart (for once). Then the chap cleaning a forme with paraffin asked if we knew about the saying, ‘Out of sorts’. Challenge accepted. We started ping ponging a few sayings, a few I’d admit to not knowing, so I thought it would be rude not to share these.

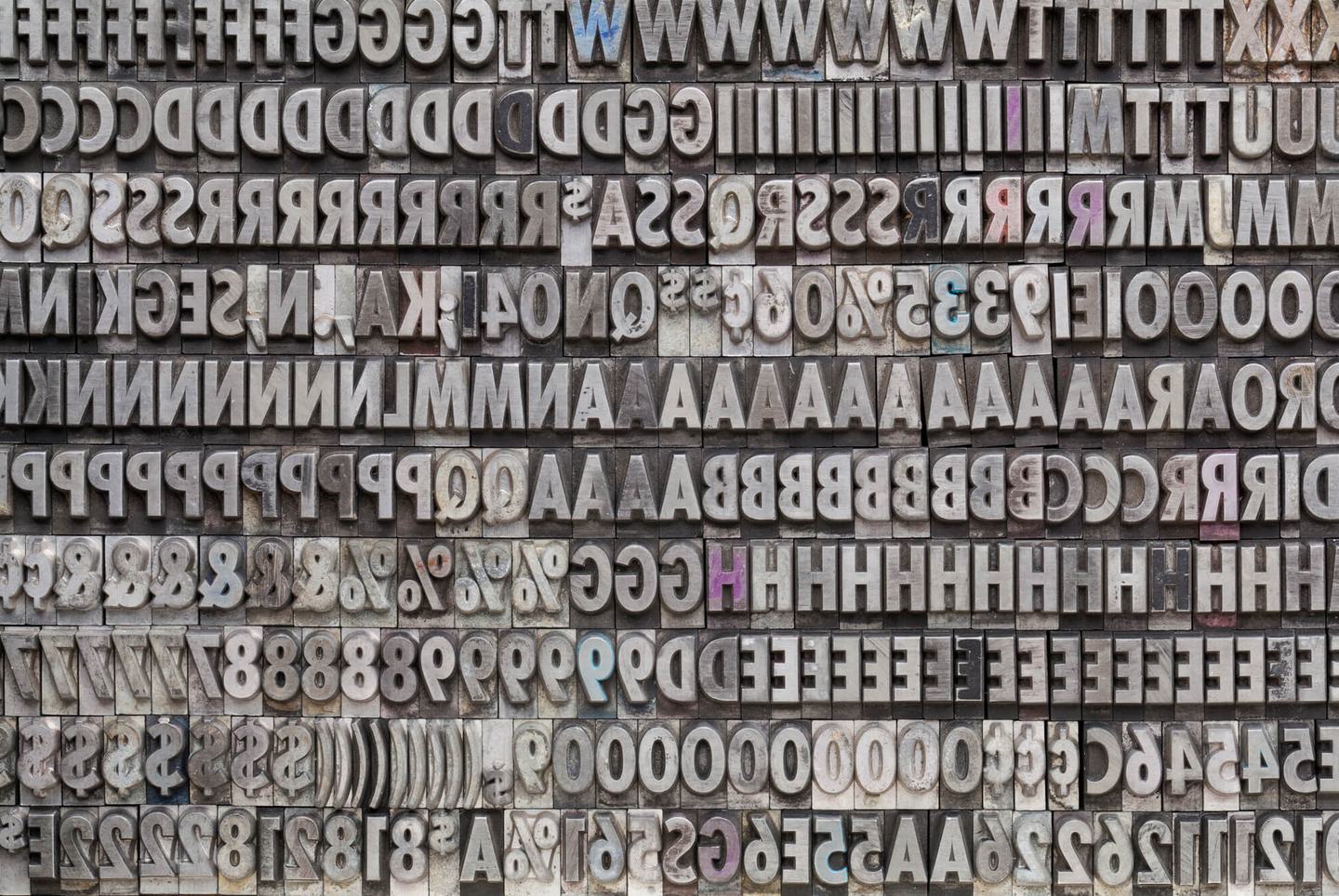

Before we begin, it is probably worth explaining how the printing process worked in the pre-digital era. Obviously, it required a lot of manual labour. Each individual character (also known as sorts) would be first placed in a composing stick and these would be transferred to a frame called a chase (a heavy steel frame). Quoins (expanding wedges) were used to position the body of set text and furniture (blocks or wood) was used to frame the characters. Finally, blank spacers were placed between each word and between lines of text to improve readability. As these spacers were typically made from lead, they were known as leads. Even today, the space between lines of text is known as leading.

Collectively, the chase, quoins, furniture and leads were called a forme.

Importantly, everything was set in reverse so when the forme was inked and impressed onto paper, the resultant image was the correct way round for the reader. The person setting the text was highly skilled and, clearly, patient as this was a time-consuming process.

Out of sorts

A sort is the name given to a piece of moveable type, representing a single character. Sorts were assembled by hand into lines of type in a chase (with blank spacers called leading) to make up a forme. The form would be used to print a page. As purchasing type was expensive, most printers only stocked enough sorts to get most jobs done. Of course, occasionally they would run out of type then they would be literally out of sorts and feeling a little frustrated.

Uppercase and lowercase

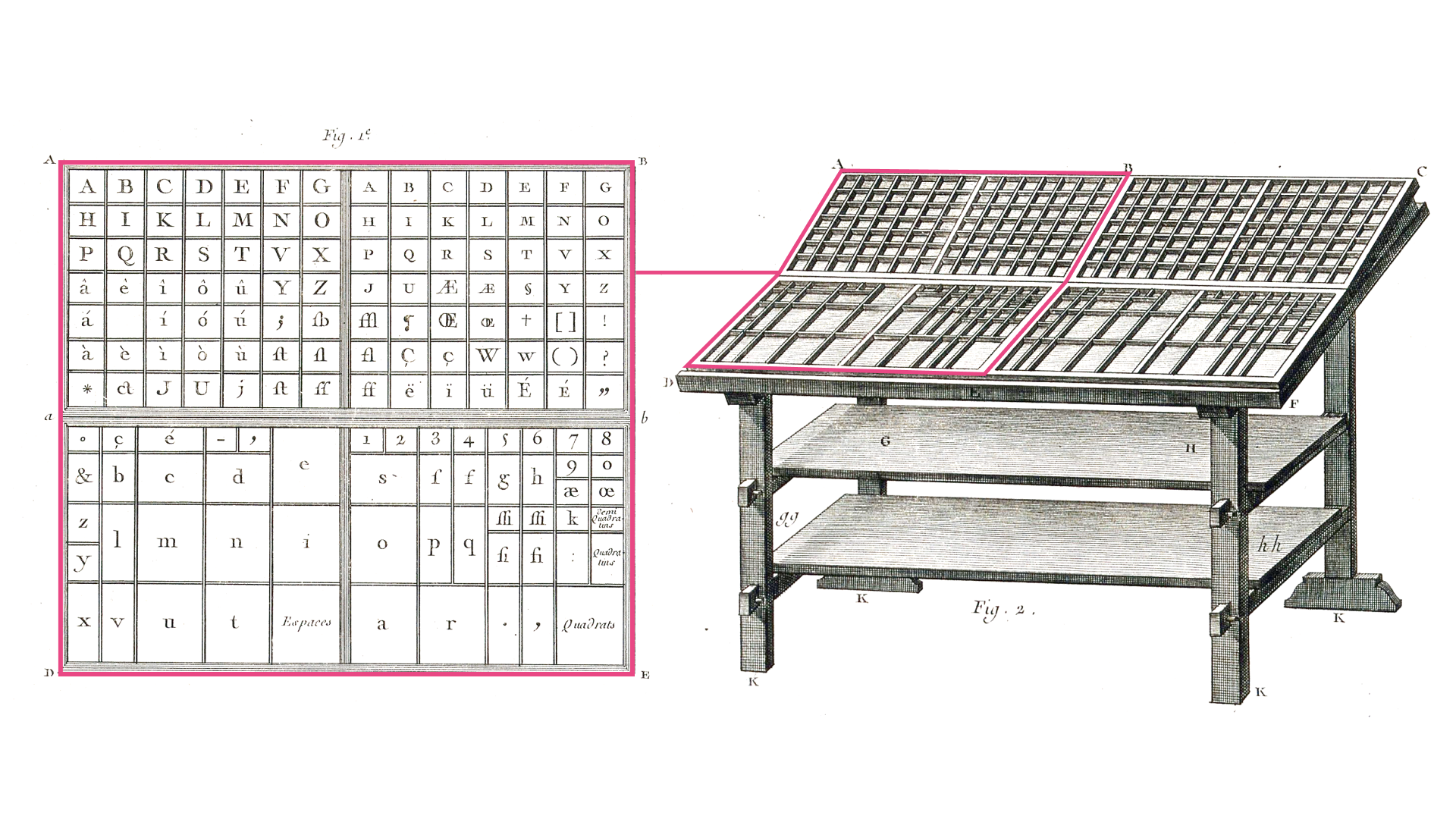

These are literally the cases the sorts would be placed in. Majuscule (capital letters) in the upper case, minuscule in the lower case. As capital letters were used less often, these were placed in the upper case which were less convenient to reach.

Image Credit: Printing. Engraving by R. Benard after L.-J. Goussier. Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark

Hot off the press

This simply refers to method invented by Ottmar Mergenthaler of casting type from hot molten lead ‘on-the-fly’ when the compositor typed the letter on a keyboard. Before his invention, the only other way to set type was by using ‘cold’ moveable type. The Linotype machine and the company got its name from the New York Tribune “You have done it, you have produce a line o’ type” (source https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/93784/10-everyday-phrases-come-printing)

Watch your Ps and Qs

This expression can mean ‘mind your manners’, ‘mind your language’ or ‘be on your best behaviour’. The p and q sorts were easy to mix up as they sat next to each other in the case. As type was set backwards it was very east to get these mixed up by selecting the wrong sort from the case. When distributing the sorts back into their cases, it was equally far too easy to mix these characters and place them in the incorrect slots.

A dab hand

Printers used a mushroom shaped instrument called a dab to apply ink onto the forme. To ensure a good impression (yes, this is another saying) was made, an even coverage of ink needed to be applied. The person responsible for this task was graced the title of ‘dab hand’ — hence our common use of someone skilled at a certain ability.

Typecast

Type was created by casting each letter from hot metal. The metal would cool to fit the mould. When an actor is chosen for a role because they fit the profile, then they have been typecast.

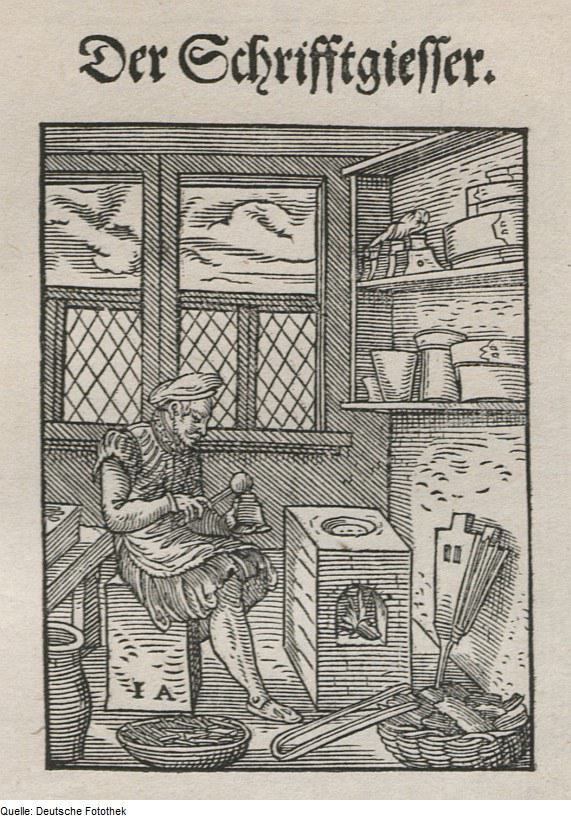

Image Credit: 1568, Woodcut print on paper by Hans Sachs. Deutsche Fotothek. Wikimedia commons

Stereotype

Building a forme was labour intensive and it could take several hours to type set a single page. A print shop wouldn’t have multiple sets of the same font, so they would need to dismantle the forme, ’distributing’ the sorts back into the type case to use the it on the next job. If the printer knew they would need to reprint the text at a later date, they would take a mould of the forme using papier-mâché or Plaster of Paris and then cast it in a single plate of hot metal. This duplicate could be stored and used to create copies at a later date.

Bonus…

Cliché

The French word for a stereotype is cliché, which unsurprisingly means a saying or remark that is very often made and is therefore not original and not interesting. Clichés were slightly different as the French only cast frequently used phrases rather than the entire text of page. These clichés would be set among individual letters to save time.

There are many English phrases we use in everyday speak, but we often don’t think about how they came to be. Hopefully these few from the Victorian print shop have whetted your appetite to seek some more. Now ‘sling your hook!’